Kid’s Chromatography

Key concepts:

Colors

Solutions

Molecules (and their polarity)

Chromatography

Primary colors

Introduction:

During my lab sessions in undergrad, I always wanted to find a way to allow children to get a more hands on experience in learning science activities. I tried to devise simple tasks at home that would get them to learn in a similar way that I learnt in the lab, along with developing a love for science. When I heard my biology professor conduct this activity with her own kids at home I thought this would be an excellent idea for all parents to do with their children at home. This chromatography lab is standard in biology, chemistry and forensics labs. It gives youngsters an experience in identifying substances as well as in incorporating lessons on polarity.

Background:

We see objects because they reflect light into our eyes. Some molecules only reflect specific colors; it is this reflected, colored light that reaches our eyes and tells our brains that we are seeing a certain color.

Often the colors that we see are a combination of the light reflected by a mixture of different-color molecules. Even though our brains perceive the result as one color, each of the separate types of color molecules stays true to its own color in the mixture. One way to see this is to find a way to separate out the individual types of color molecules from the mixture—to reveal their unique colors.

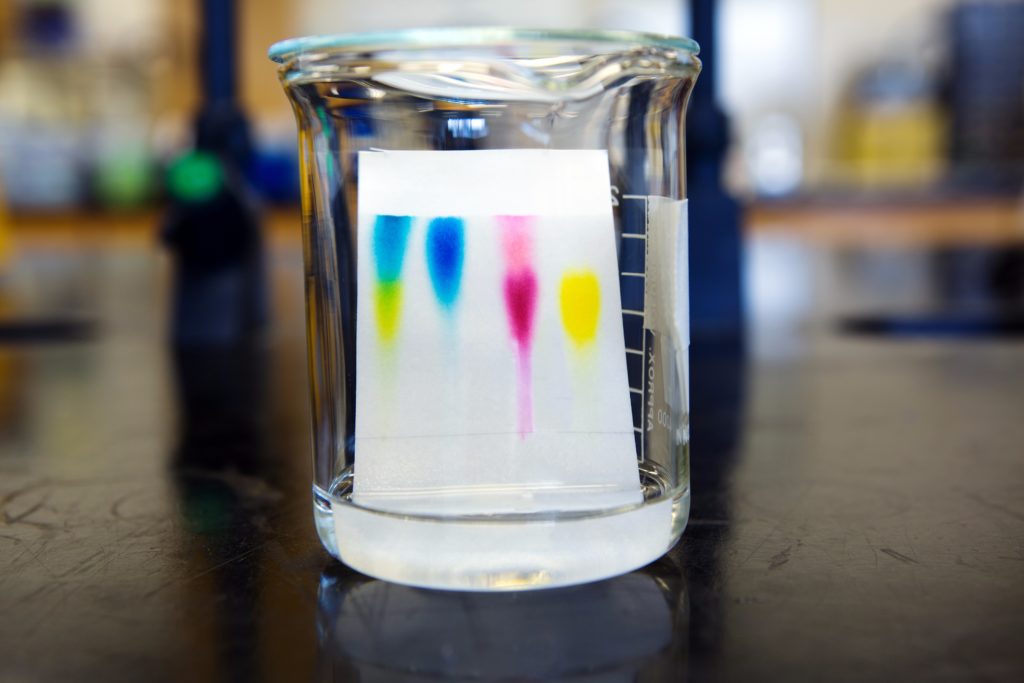

Paper chromatography is a method used by chemists to separate the constituents (or parts) of a solution. The components of the solution start out in one place on a strip of special paper. A solvent (such as water, oil or isopropyl alcohol) is allowed to absorb up the paper strip. As it does so, it takes part of the mixture with it. Different molecules run up the paper at different rates. As a result, components of the solution separate and, in this case, become visible as strips of color on the chromatography paper. Will your marker ink show different colors as you put it to the test?

Materials:

Two white coffee filters

Scissors

Ruler

Drawing markers (not permanent): brown, yellow and any other colors you would like to test

At least two pencils (one for each color you will be testing)

At least two tall water glasses (one for each color you will be testing), four inches or taller

Water

Two binder clips or clothespins

Drying rack or at least two additional tall water glasses (one for each color you will be testing)

Pencil or pen and paper for taking notes

Preparation:

Carefully cut the coffee filters into strips that are each about one inch wide and at least four inches long. Cut at least two strips, one to test brown and one to test yellow. Cut an extra strip for each additional color you would like to test. How do you expect each of the different colors to behave when you test it with the paper strip?

Draw a pencil line across the width of each paper strip, about one centimeter from the bottom end.

Take the brown marker and a paper strip and draw a short line (about one centimeter) on the middle section of the pencil line. Your marker line should not touch the sides of your strip.

Use a pencil to write the color of the marker you just used on the top end of the strip. Note: Do not use the colored marker or pen to write on the strips, as the color or ink will run during the test.

Repeat the previous three steps with a yellow marker and then all the additional colors you would like to test.

Hold a paper strip next to one of the tall glasses (on the outside of it), aligning the top of the strip with the rim of the glass, then slowly add water to the glass until the level just reaches the bottom end of the paper strip. Repeat with the other glass(es), keeping the strips still on the outside and away from the water. What role do you think the water will play?

Procedure:

Fasten the top of a strip (the side farthest from the marker line) to the pencil with a binder clip or clothespin. Pause for a moment. Do you expect this color to be the result of a mixture of colors or the result of one color molecule? If you like, you can make a note of your prediction now.

Hang the strip in one of the glasses that is partially filled with water by letting the pencil rest on the glass rim. The bottom end of the strip should just touch the water level. If needed, add water to the glass until it is just touching the paper. Note: It is important that the water level stays below the marker line on the strip.

Leave the first strip in its glass as you repeat the previous two steps with the second strip and the second glass. Repeat with any additional colors you are testing.

Watch as the water rises up the strips. What happens to the colored lines on the strips? Does the color run up as well? Do you see any color separation?

When the water level reaches about one centimeter from the top (this may take up to 10 minutes), remove the pencils with the strips attached from the glasses. If you let the strips run too long, the water can reach the top of the strips and distort your results.

Write down your observations. Did the colors run? Did they separate in different colors? Which colors can you detect? Which colors are on the top (meaning they ran quickly) and which are on the bottom (meaning they ran more slowly)?

Hang your strips to dry in the empty glasses or on a drying rack. Note that some colors might keep running after you remove the strips from the water. You might need longer strips to see the full spectrum of these colors. The notes you took in the previous step will help you remember what you could see in case the colors run off the paper strip. Look at your strips. How many color components does each marker color have? Can you identify which colors are the result of a mixture of color components and which ones are the result of one hue of color molecule? Are individual color components brightly colored or dull in color? How many different colors can you detect in total?

Extra: Most watercolor marker inks are colored with synthetic color molecules. Artists often like to work with natural dyes. It is fairly easy to make your own dye from colorful plants such as blueberries, red beets or turmeric. To make your own dye, have an adult help you finely chop the plant material and place it in a saucepan. And add just enough water to cover the plant material. Let the mixture simmer covered on the stove for approximately 10 to 15 minutes. If, at this point, the color of your liquid is too faint, you might want to remove the lid of the saucepan and continue boiling until some liquid has evaporated and a more concentrated color is obtained. Let it cool and strain when needed. Now you have natural dye. (Handle with caution, as it can stain surfaces and materials.) To investigate the color components of this dye, repeat the previous procedure but replace the marker line with a drop of natural dye. A dropper will help create a nice drop. Let the drop of dye dry before running the paper strip. Would the color of your natural dye be the result of a mixture of color molecules or one specific color molecule? Does the marker of the same color as your natural dye run in a similar way as your natural dye does?

Extra: In this activity you used water-soluble markers in combination with water as a solvent. You can test permanent markers using isopropyl rubbing alcohol as a solvent. Do you think similar combinations of color molecules are used to color similar-colored permanent markers?

Extra: You can investigate other art supplies, including paints, pastels or inks in a similar way. Be sure to always choose a solvent that dissolves the material that is being tested to run the chromatography test. Isopropyl rubbing alcohol, vegetable oil and salt water are some examples of solvents used to perform paper chromatography tests for different substances.

Observations and results:

Did you find that brown is made up of several types of color molecules, whereas yellow only showed a single yellow color band?

Marker companies combine a small subset of color molecules to make a wide range of colors, much like you can mix paints to make different colors. But nature provides an even wider range of color molecules and also mixes them in interesting ways. As an example, natural yellow color in turmeric is the result of several curcuminoid molecules. The brown pigment umber (obtained from a dark brown clay) is caused by the combination of two color molecules: iron oxides (which have a rusty red-brown color) and manganese oxides (which add a darker black-brown color).

In this activity you investigated the color components using coffee filters as chromatography paper. Your color bands might be quite wide and artistic, whereas scientific chromatography paper would yield narrow bands and more-exact results.

Courtesy of Science Buddies

Reading your website is big pleasure for me, it deserves to go viral, you need some initial traffic only.